Finding Nature's Armored Architects

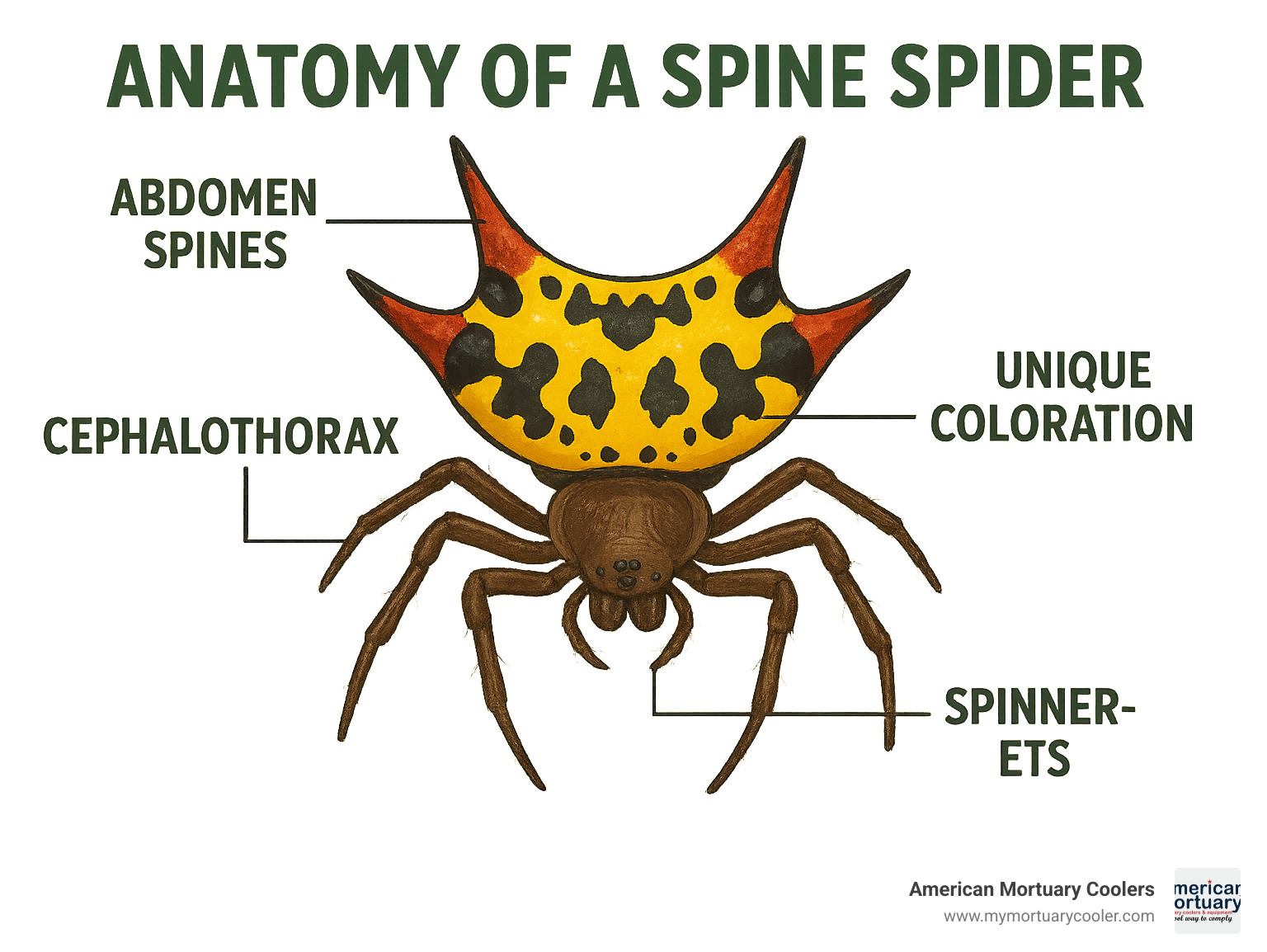

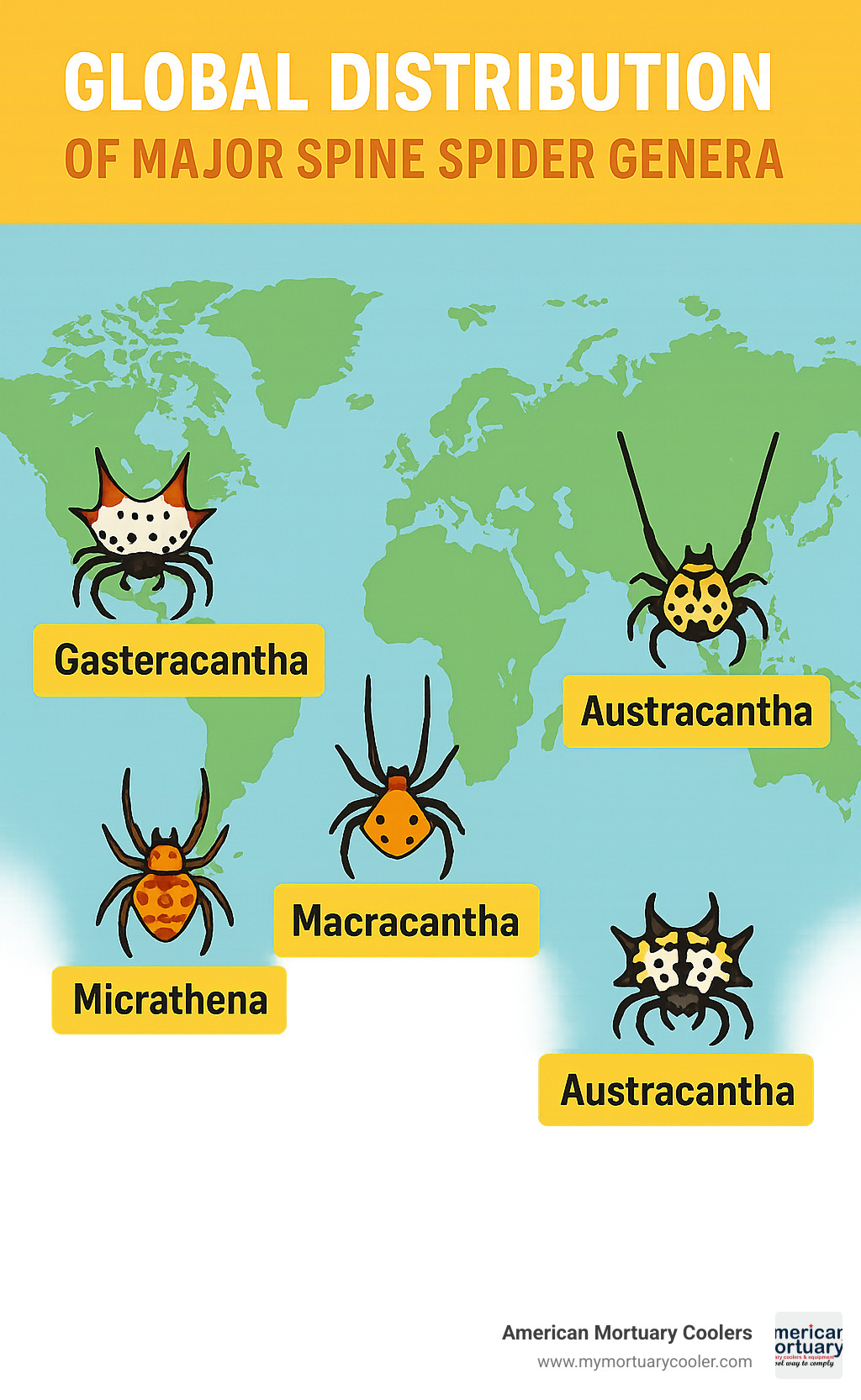

A spine spider is an orb-weaver spider characterized by prominent spines protruding from its abdomen, typically belonging to genera such as Gasteracantha, Micrathena, or Macracantha in the family Araneidae. While not a formal taxonomic classification, the term encompasses several distinct species known for their defensive spiny projections and colorful abdomens.

Quick Facts About Spine Spiders:

- Common Genera: Gasteracantha, Micrathena, Macracantha

- Size: Females typically 5-10mm (body length), males much smaller (2-3mm)

- Distinctive Feature: 4-12 prominent spines on abdomen

- Venom: Not medically significant to humans

- Habitat: Woodland edges, gardens, trails in tropical and subtropical regions

- Web Type: Orb-shaped with occasional silk tufts as decorations

The world of spine spiders represents one of nature's most fascinating examples of defensive evolution. These distinctive arachnids have developed their characteristic spiny projections as protection against predators, while simultaneously evolving some of the most vibrant color patterns found in the spider world. Despite their intimidating appearance, spine spiders are harmless to humans and actually provide valuable ecosystem services by controlling flying insect populations.

I'm Mortuary Cooler, and while my expertise primarily lies in mortuary equipment solutions, I've developed a fascination with spine spider species through years of encountering these remarkable creatures in facilities across diverse geographic regions. My experience has taught me that understanding the natural world around us—including spine spiders—helps us appreciate the intricate balance that sustains all life.

Quick look at spine spider:

Why This Guide Matters

Whether you're a nature enthusiast, a concerned homeowner, or simply curious about these distinctive arachnids, understanding spine spiders is valuable for several reasons. First, these creatures are often misidentified and unnecessarily feared due to their intimidating appearance. Second, they play important ecological roles in controlling insect populations in gardens and natural areas. Finally, their unique adaptations and behaviors represent fascinating examples of evolutionary success.

This guide aims to provide comprehensive information for readers across the globe, from the southeastern United States where Gasteracantha cancriformis is common, to Southeast Asia where Macracantha hasselti displays its striking colors. By the end of this article, you'll be able to confidently identify various spine spider species, understand their ecological importance, and appreciate these remarkable creatures for the beneficial role they play in our environment.

What Is a Spine Spider?

Ever noticed those eye-catching spiders with what look like tiny armor spikes? That's what we call a spine spider. While not an official scientific category, this term describes several types of orb-weaving spiders from the Araneidae family that sport distinctive spiny projections on their abdomens. These spines aren't just for show – they're nature's way of saying "don't eat me!" to predators like birds and larger insects.

The spider world is full of these spiny characters, with the most common ones belonging to a few main groups. The Gasteracantha genus (whose name literally means "thorny belly" in Greek) includes many colorful species. If you're in the Americas, you might spot Micrathena species with their smaller but equally effective spines. Asian regions are home to the impressive Macracantha with their longer spines, while Australia boasts its own Austracantha jewel spiders that glitter in the sunlight. There's also the Poecilopachys genus, which includes the fascinating Two-spined or Enamelled Spider.

These architectural wonders go by many names depending on where you find them. You might hear them called spiny-backed orb-weavers, jewel spiders, or thorn spiders. In Australia, some are affectionately known as Christmas spiders because of their festive colors. Some Gasteracantha species even earned the nickname "smiley face spiders" due to the pattern on their backs – nature's own emoji!

From a scientific standpoint, spine spiders fit neatly into the animal kingdom's organization system. They're arthropods (joint-legged animals) in the arachnid class, specifically orb-weaving spiders in the Araneidae family. While they may look intimidating, these spiders represent what renowned arachnologist Dr. William Eberhard describes as "a fascinating example of convergent evolution" – different spider groups independently developing similar defensive features when faced with similar threats.

What makes these spiders truly remarkable isn't just their spiky appearance, but how this simple adaptation has helped them thrive across multiple continents and ecosystems. Their distinctive silhouette is instantly recognizable to naturalists and garden enthusiasts alike – proving that sometimes in nature, the best defense is a good offense.

How to Identify Spine Spiders: Physical Characteristics

When you stumble across a spine spider in your garden or on a woodland hike, you'll know it immediately by its distinctive armored look. These fascinating creatures aren't trying to hide—they're showing off nature's perfect blend of form and function.

The most eye-catching feature of any spine spider is, of course, those remarkable spines jutting from their abdomens. Different species sport different arrangements—Gasteracantha species typically flaunt six spines (three on each side), while Micrathena might show off 4-10 spines in various patterns. If you spot extremely long rear spines, you're likely looking at a Macracantha species from Asia. The Two-spined Spider (Poecilopachys australasia) keeps things minimal with just two prominent white spines.

Looking at their body shape reveals another clue—most spine spiders have abdomens wider than they are long, creating distinctive geometric silhouettes. The Gasteracantha cancriformis displays a crab-like, hexagonal abdomen, while Micrathena gracilis features a more elongated, pyramid-shaped form. The triangular abdomen of Macracantha hasselti with its extremely long rear spines makes for an unmistakable profile.

One of the most remarkable aspects of these spiders is their dramatic sexual dimorphism. The females steal the show—they're substantially larger (5-10mm) with bold spines and vibrant coloring. Males, by contrast, are tiny fellows (just 2-3mm) with reduced spines and subtle coloration. As one researcher humorously noted: "Most people who see them find males only when they're courting in the webs of females"—essentially, males are easily overlooked unless they're on a date!

Female spine spiders are nature's living jewels. Gasteracantha species often display sunshine-yellow, stark white, or brilliant red abdomens with contrasting black spots. Micrathena species might appear in neat black and white, cheerful yellow, or gleaming silver combinations. The Macracantha hasselti females are particularly striking with bright orange abdomens decorated with 12 perfect black spots.

According to field data from the Missouri Department of Conservation, "The spined micrathena female can reach up to about 3/8 inch (approx. 9.5 mm) in length, while males are only about 1/8 inch (approx. 3 mm)." This dramatic size difference is consistent across most spine spider species.

| Characteristic | Gasteracantha | Micrathena |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Spines | Usually 6 | 4-10 |

| Abdomen Shape | Wider than long, hexagonal | Variable, often pyramid-shaped |

| Female Size | 5-9mm long, 10-13mm wide | 3-10mm long |

| Male Size | 2-3mm | 2-3mm |

| Geographic Range | Tropical regions worldwide, one species in Americas | Primarily Americas |

| Web Decoration | Often has silk tufts (stabilimenta) | Rarely has silk tufts |

| Color Pattern | Often yellow/white with black spots | Often black/silver/yellow |

Spine Spider vs. Crab Spider

Despite sometimes earning the nickname "crab-like orb-weavers," spine spiders shouldn't be confused with true crab spiders from the Thomisidae family. The differences become clear when you know what to look for.

While both might have a somewhat crab-like appearance, true crab spiders have smooth, rounded abdomens without any spines, quite unlike the armored look of our spiny friends. Their hunting styles couldn't be more different either—spine spiders are web architects who patiently wait for prey to become entangled in their orb webs, while crab spiders are stealthy ambush hunters who don't build webs at all, preferring to hide on flowers waiting for unsuspecting insect visitors.

You can also tell them apart by their eye arrangement (spine spiders have the typical orb-weaver pattern with eight eyes in two rows) and leg position (crab spiders hold their front two pairs of legs extended sideways like, well, a crab, while spine spiders maintain a more conventional spider posture).

Key Field Marks of a Spine Spider

When you're out spider-watching, several distinctive characteristics will help you spot and identify a spine spider:

The relative length and shape of spines offer important clues about which genus you're observing. Gasteracantha species typically display six spines of roughly equal length, while Macracantha hasselti shows off those dramatically elongated rear spines. Micrathena gracilis takes it to another level with ten spines of varying lengths.

Many species feature beautiful spot patterns on their abdomens that help with identification. Gasteracantha cancriformis typically sports 12 black spots arranged in two neat rows, while Macracantha hasselti displays 12 black spots against a vibrant orange background. These patterns and colors can vary depending on where in the world you find them.

Web location and structure provide additional clues—look for orb webs strategically positioned in woodland edges, along trails, or among garden shrubs. Many hikers have had the surprise experience of walking face-first into these webs, as they're often positioned at just the wrong height across paths! Some species add artistic flair with silk tufts called stabilimenta woven into their webs.

When in their web, spine spiders typically hang upside-down in the center, with their spinnerets pointing upward and legs tucked close to their bodies when disturbed. According to community science data, "87% of the time, Gasteracantha cancriformis spiders are sighted in a spider web," making web presence a reliable field mark for this fascinating group.

Major Spine Spider Species Around the World

The world of spine spiders is wonderfully diverse, with fascinating species scattered across tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. Let's take a journey to meet some of these remarkable armored architects!

Gasteracantha cancriformis (Spiny-backed Orb-weaver)

The spiny-backed orb-weaver is the celebrity of the spine spider world in the Americas. Female spiders sport six distinctive black spines (with the rear pair often stretching longer than the others) on an abdomen that's wider than it is long—typically 5–9 mm in length but 10–13 mm wide.

These little jewels come in various fashion choices, from crisp white or bright yellow with black polka dots to eye-catching varieties with red spines. They've made themselves at home throughout the southern United States, across Central America, and throughout the Caribbean islands.

Community science enthusiasts have documented 61 confirmed sightings across seven countries and ten U.S. states—proof that these little architects have established quite the real estate empire!

Micrathena gracilis (Spined Micrathena)

If you're hiking in eastern North American woodlands, you might come face-to-web with the spined Micrathena. These distinctive spine spiders showcase ten sharp black spines arranged around a striking black and white abdomen that forms a pyramid shape when viewed from the side.

The ladies of this species reach about 9.5mm in body length and have a particular fondness for woodland edges and trail borders. There's something rather poetic about how nature connects different species—as the Missouri Department of Conservation points out, "Hummingbirds, vireos, and warblers steal orb-web silk for nest-building," creating an unexpected relationship between these spiders and their feathered neighbors.

Poecilopachys australasia (Two-spined Spider)

Down under in Australia and parts of Oceania, the two-spined spider breaks the multi-spine trend with just two prominent white spines—a minimalist in the spine spider world! These unusual arachnids display vibrant colors including red, orange, and yellow on their rounded 7mm abdomens.

Australian Museum researchers describe them as "one of the most curious and beautiful of all spiders," and they're not just pretty faces. These industrious creatures have the remarkable habit of eating their entire web each morning after a night of hunting—talk about cleaning up after yourself!

Macracantha hasselti (Hasselt's Spiny Spider)

Southeast Asia hosts what might be the most spectacular of all spine spiders—Macracantha hasselti. These showstoppers feature six spines, but it's the rear pair that steals the spotlight, extending dramatically beyond the spider's body like neat rapiers.

Their bright orange triangular abdomens decorated with 12 precise black spots make them look like living jewelry. You'll find them from India through Southeast Asia to Indonesia, their carapaces beautifully adorned with dense white hairs.

Austracantha minax (Australian Jewel Spider)

Australia's own jewel spider sports six short but robust spines and dresses in a dazzling pattern of black, white, orange, and yellow. What makes these spine spiders particularly interesting is their occasional communal web-building behavior—sometimes they're the spider equivalent of apartment dwellers!

These adaptable arachnids have made themselves at home in environments ranging from pristine forests to suburban gardens, showing remarkable flexibility in habitat choice.

Spinepeira schlingeri

Sometimes rarity makes a species special, and Spinepeira schlingeri certainly qualifies. This lone species in its genus was only described by Levi in 1995. While researchers still have much to learn about this uncommon spider, its taxonomic uniqueness earns it a place in any thorough discussion of spine spiders.

The genus Gasteracantha currently boasts 69 recognized species and 18 subspecies according to the World Spider Catalog, making it one of the more diverse families in the spine spider world.

New World Spine Spider Highlights

In the Americas, spine spiders are primarily represented by Gasteracantha cancriformis and various Micrathena species, each with their own fascinating characteristics.

These New World architects have established clear geographic boundaries, with Gasteracantha cancriformis claiming territory from the southern United States through Central America and the Caribbean, while Micrathena species stretch from Canada all the way down to South America.

They're definitely outdoor enthusiasts—field data shows "Gasteracantha cancriformis is most often sighted outdoors, with 65 outdoor and 3 indoor sightings reported." Community science data reveals activity peaks in May (11 sightings), March (9), and January (7), giving us clues about their seasonal patterns.

I've always found it clever how Micrathena species position their webs along woodland trails—they're essentially setting up their dining tables along nature's insect highways where flying bugs are naturally channeled!

Old World Spine Spider Diversity

The greatest diversity of spine spiders flourishes in tropical Asia, Africa, and Australia, where evolution has crafted an impressive array of spine configurations and color patterns.

Asian jewel spiders from India through Southeast Asia showcase nature's creative variations on the spine spider theme. Meanwhile, Australia's two-spined enamelled spider (Poecilopachys australasia) demonstrates unusual behaviors like daily web consumption and rapid color changes that likely help it avoid becoming someone else's lunch.

Macracantha hasselti takes spine defense to the extreme with its impressive rear spines that can stretch longer than the spider's entire body—imagine wearing a hat twice as tall as you are!

Australia contributes its unique specimens to the spine spider family album, including the striking Australian jewel spider (Austracantha minax) with its bold black and yellow warning colors.

According to taxonomic records, tropical Asia hosts the greatest number of Gasteracantha species. Interestingly, a 2019 molecular study revealed that Gasteracantha is paraphyletic relative to several allied genera—a fancy way of saying that spider family trees are still being sorted out by researchers, with some branches needing rearrangement.

Life Cycle, Behavior & Ecological Role

The fascinating world of spine spiders reveals a rich mix of adaptations that have allowed these distinctive arachnids to thrive across tropical and subtropical environments worldwide. From their unique reproductive strategies to their impressive architectural skills, these small predators play surprisingly important roles in their ecosystems.

Egg Sac and Development

The life of a spine spider begins inside a distinctive egg sac crafted by the female. For species like Gasteracantha cancriformis, this nursery takes the form of a flattened mass of bright yellowish-green silk, sometimes decorated with a dark green vertical stripe. Rather than keeping this precious package in her web, the mother typically hides it away in nearby foliage.

When spring arrives, tiny spiderlings emerge and start on their first trip—ballooning. Using silken threads as parachutes, these baby spiders catch the breeze and disperse across the landscape. Throughout summer, they grow steadily, with females reaching their full impressive size by late summer or early fall, complete with their characteristic spiny defenses.

Web-Building Behavior

As members of the orb-weaver family, spine spiders are master architects. They construct the classic wheel-shaped webs that many of us associate with spiders, typically building in open areas between trees or shrubs. Many species are perfectionists, tearing down and rebuilding their webs daily to ensure optimal hunting conditions.

The spider typically positions itself at the center of its creation, hanging upside-down and waiting patiently for prey. Some species add an artistic touch with distinctive silk tufts called stabilimenta. These decorations may serve as visual warnings to birds, preventing them from accidentally flying through and destroying the spider's hard work.

Perhaps most remarkable is the Two-spined Spider (Poecilopachys australasia), which takes recycling to an extreme. Each morning, this thrifty arachnid consumes its entire web after a night of hunting, efficiently recycling the silk proteins to build a fresh web the following evening.

Prey Capture and Diet

As predators, spine spiders play crucial ecological roles in controlling insect populations. Their primary diet consists of small flying insects that many humans consider pests—mosquitoes, gnats, and flies. Their orb webs act as effective interceptors, catching insects in mid-flight.

When prey hits the web, the spider responds with impressive speed, rushing to immobilize its catch with silk and venom. As one observer noted, "It would be easy to dismiss the importance of these tiny predators, but once you've been plagued by gnats and mosquitoes, you become thankful for their role." Indeed, many gardeners welcome these spiny neighbors precisely because they help keep annoying insect populations in check.

Color Change and Camouflage

Some spine spider species possess remarkable abilities to change their appearance. Poecilopachys australasia, for example, can change color relatively quickly, possibly as a strategy to confuse potential predators. Many species have evolved bright warning coloration—a phenomenon known as aposematism—effectively advertising their defensive spines to would-be predators.

The survival strategies vary by species. Some are bold daylight hunters, displaying their vibrant colors openly as they sit in their webs. Others take a more cautious approach, hiding under leaves during daylight hours and emerging as active web-builders only when darkness falls.

Stridulation Defense

Beyond their impressive spines, some spine spiders have developed additional defensive mechanisms. Certain Gasteracantha species use stridulation—making sounds by rubbing body parts together—as an antipredator tactic. This acoustic warning may serve as an additional deterrent, particularly against vertebrate predators like birds.

Research on antipredator stridulation in spiders suggests this behavior may have evolved independently in multiple spider lineages, highlighting its effectiveness as a defensive strategy across the spider world.

Predators and Ecosystem Services

Despite their formidable defenses, spine spiders aren't invincible. They face numerous predators including birds (particularly warblers and hummingbirds), lizards and other reptiles, larger spiders, predatory insects, and parasitoid wasps that target their eggs.

Their ecological importance extends beyond pest control. These spiders serve as food for numerous insectivorous animals, their webs contribute to the complex food web of forest edge habitats, and some birds even harvest their silk as premium building material for nests.

Spine Spider Courtship & Mating

The reproductive behavior of spine spiders highlights one of the animal kingdom's most dramatic examples of sexual dimorphism. The tiny males (typically just 2-3mm) must somehow court females several times their size (5-10mm) without becoming dinner.

Males approach female webs with understandable caution, often plucking web strands in specific patterns. These "courtship vibrations" help identify the male as a potential mate rather than prey. Even so, the risk is considerable—males can easily be mistaken for a snack and consumed. Some clever males wait at the edge of a female's web until she molts and is temporarily vulnerable before making their move.

The actual mating process is brief, minimizing risk to the male. After successful sperm transfer, males of Gasteracantha cancriformis typically die approximately six days later, while females die shortly after producing their egg sac. As one researcher observed: "The extreme sexual dimorphism in spine spiders represents one of the most dramatic examples of male/female size disparity in the spider world, reflecting different selective pressures on the sexes."

Unique Web Architecture of a Spine Spider

The webs of spine spiders are true architectural marvels that reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement. Their classic wheel-shaped (orb) design features radiating spokes and concentric capture spirals, with the hub (center) often reinforced where the spider sits. Web diameter typically ranges from 20-40cm depending on species—a remarkable structure for such a small architect.

Many Gasteracantha species add artistic flourishes in the form of stabilimenta—small silk tufts or balls incorporated into their webs. These decorations may serve multiple purposes: visual warnings to prevent birds from flying through the web, attractants for insect prey, or camouflage for the spider waiting at the center.

The engineering behind these webs is equally impressive. Spine spiders produce multiple types of silk with different properties—strong, non-sticky silk for the structural "spokes" and extremely elastic, sticky silk for the capture spiral that traps prey. Some species can even produce silk of different colors, such as the yellow-green silk used for egg sacs.

Web-building patterns vary across species. Many Gasteracantha maintain webs throughout the day, while Poecilopachys australasia builds webs at night and consumes them in the morning. Micrathena species typically maintain their webs during daylight hours.

According to field observations, "Birds and hikers often blunder into webs, prompting the spider's escape drop" via a single long silk thread that allows the spider to quickly descend and hide when disturbed—a simple but effective escape strategy that has served these spiny architects well for millions of years.

Safety & Human Interaction

Despite their intimidating appearance with prominent spines and bright warning colors, spine spiders are actually gentle neighbors in our natural world. Their fearsome looks belie their harmless nature when it comes to humans.

Venom and Bite Potential

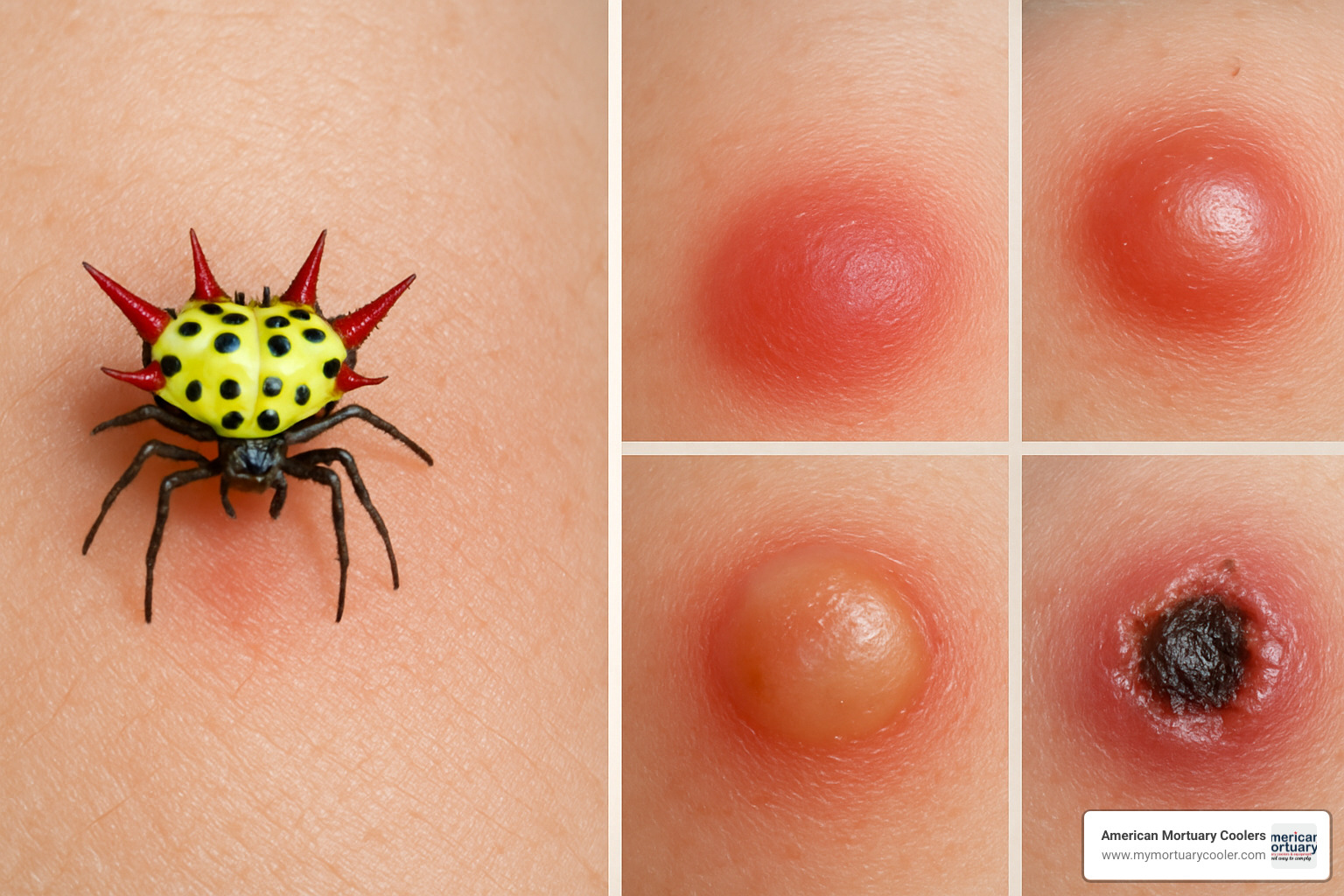

The venom of spine spiders is specifically designed for one purpose: to subdue tiny insect prey. For humans, this venom poses virtually no medical concern.

Bites from these spiny architects are extraordinarily rare events. Why? These shy creatures aren't interested in confrontation with giants like us. When disturbed, their first instinct is to flee rather than fight, typically dropping from their web on a silken escape line. Even if a bite were to occur, their small fangs struggle to penetrate human skin.

Should you experience the rare event of a spine spider bite, you might notice minor localized pain (similar to a mild bee sting), perhaps accompanied by slight redness or swelling at the bite site. These symptoms typically resolve completely within 24 hours without any treatment. No serious medical complications have ever been documented from these fascinating creatures.

Benefits to Humans

Far from being creatures to fear, spine spiders actually provide several valuable services to us humans.

These diligent weavers serve as nature's pest control specialists, capturing and consuming significant numbers of flying insects including mosquitoes and flies. A single spine spider can catch dozens of insects daily in its intricate web. This natural insect management helps reduce populations of both disease-carrying and simply annoying bugs around our homes and gardens.

The presence of spine spiders often signals a healthy ecosystem. Their abundance can reflect balanced insect population levels, and they contribute significantly to the biodiversity of both cultivated and wild spaces. I've often noticed that gardens with healthy spine spider populations tend to have fewer pest problems overall.

These distinctive arachnids also offer wonderful educational opportunities. Their eye-catching appearance makes them perfect subjects for introducing children and adults alike to the wonders of nature. They beautifully demonstrate principles of evolutionary adaptation, predator-prey relationships, and sexual dimorphism. And those magnificent webs? They're masterclasses in natural engineering principles that have even inspired human designers.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

Let's clear up some common misunderstandings about spine spiders:

Those intimidating spines can't sting or inject venom – they're purely defensive structures that make the spider difficult for predators to swallow. The bright, attention-grabbing colors aren't advertising extreme toxicity (as they might in some animals) but are warning coloration to deter predators from attempting to eat that spiny abdomen. And contrary to what some might assume, these spiders are not aggressive toward humans – they're actually quite shy and prefer to retreat when disturbed.

As renowned arachnologist Dr. Linda Rayor once noted: "The elaborate defensive adaptations of spine spiders—from spines to bright colors—have unfortunately contributed to unwarranted fear, when in reality these are among the most harmless spiders you're likely to encounter."

Preventing Unwanted Encounters with a Spine Spider

If you'd prefer to maintain a respectful distance from spine spiders, here are some helpful tips:

When hiking woodland trails, especially in late summer when females reach their largest size, watch for webs positioned at face height. These distinctive orb-shaped structures are typically built in open areas, often incorporating visible silk tufts that catch the light. They're frequently positioned across trails or between shrubs.

Should a spine spider build its web in an inconvenient location around your home, consider a gentle relocation rather than destruction. Using a stick, carefully collect the spider and web, then move it to a nearby shrub or tree away from human traffic. It's best to avoid handling the spider directly to prevent causing it stress.

At our American Mortuary Coolers facilities across Tennessee and the Southeast, we often remind our staff: "A spine spider outside is a natural pest controller. A spine spider relocated is better than a spine spider squished." These remarkable creatures deserve our respect rather than our fear, as they go about their important work in our shared environment.

For more information about how we approach ecological considerations in our facilities, visit our article on mortuary equipment.

Frequently Asked Questions about Spine Spiders

Are spine spiders dangerous to humans?

Despite their somewhat intimidating appearance, spine spiders are completely harmless to humans. I've encountered hundreds of these fascinating creatures during my career, and I can confidently say their fearsome look is all show and no substance.

Their venom is specifically designed for one purpose: immobilizing tiny insects that get caught in their webs. It simply doesn't pack enough punch to cause any medical concerns for humans. In fact, these spiders are remarkably shy – they'd much rather drop away on a silken escape line than confront a human.

In the extremely rare event that you somehow manage to get bitten (you'd practically need to trap one against your skin), you might experience a mild sensation similar to a mosquito bite – perhaps a tiny bit of redness or slight swelling that disappears within a day without any treatment needed.

As my colleague who studies arachnids often says, "These spiders invested in armor, not weapons." Their entire defensive strategy revolves around looking intimidating rather than actually being dangerous.

How can I quickly tell a spine spider from other orb-weavers?

Spotting a spine spider among other orb-weavers is actually quite simple once you know what to look for. The most obvious giveaway is right in the name – those distinctive spines jutting out from their abdomens. No other orb-weavers have this feature, making identification pretty straightforward.

Beyond the spines, pay attention to their unique body shape. While most spiders have oval abdomens, spine spiders sport abdomens that are wider than they are long, often with a geometric appearance that might remind you of a tiny crab or a star. Many species display bright warning colors – yellows, whites, or oranges with contrasting black spots – another helpful identification clue.

Their web placement is also distinctive. You'll typically find their orb webs strung in open areas between vegetation at about eye level (unfortunately for hikers who might walk face-first into them!). Many species add special silk decorations called stabilimenta to their webs, which look like small silk tufts or zigzags.

When at rest, spine spiders hang upside-down in the center of their webs with their spinnerets pointing upward – a characteristic pose that helps distinguish them from other web-building spiders.

Do spine spiders help control garden pests?

Absolutely! Spine spiders are nature's own pest control specialists, and they work for free. Having them in your garden is like employing a 24/7 insect management team that never takes a break.

Their beautifully engineered orb webs function as highly effective insect traps, capturing mosquitoes, gnats, flies, and small moths – many of which can damage plants or bother you during outdoor activities. A single spine spider can catch dozens of insects daily, quietly reducing pest populations without any chemicals or human intervention.

I've watched gardeners who initially feared these distinctive spiders gradually come to appreciate them as valuable allies. As one gardening enthusiast told me, "I used to knock down their webs until I noticed how many mosquitoes disappeared after letting the spiders stay. Now I consider them part of my gardening team!"

Their presence generally indicates a healthy ecosystem with balanced predator-prey relationships. So if you spot a spine spider in your garden, consider yourself lucky – you've got a tireless worker helping maintain the natural balance of your outdoor space.

At American Mortuary Coolers, we've learned to appreciate these helpful creatures around our facilities. While our expertise is in mortuary equipment, we've gained an appreciation for the natural world that surrounds us. As we like to remind our staff when they encounter these spiders: "A spine spider outside is a natural pest controller – and a relocated spider is better than a squished spider."

Conclusion

As we've journeyed through the fascinating world of spine spiders, we've finded creatures that are as beautiful as they are misunderstood. From the striking Gasteracantha cancriformis with its crab-like appearance to the neat Micrathena gracilis with its crown of spines, these remarkable arachnids showcase nature's endless creativity.

Despite their intimidating appearance, spine spiders are gentle neighbors that want nothing more than to spin their intricate webs and catch a few mosquitoes. Their defensive spines and bright warning colors aren't meant for us – they're simply trying to avoid becoming a bird's breakfast!

Here at American Mortuary Coolers, we've developed an unexpected appreciation for these little architects. While crafting mortuary refrigeration solutions is our primary focus, we can't help but admire the spine spiders that occasionally build their masterpieces around our Tennessee facilities. There's something humbling about watching these tiny engineers at work, reminding us that innovation comes in all sizes.

If you've enjoyed learning about these fascinating creatures, consider becoming a citizen scientist! Websites like iNaturalist and BugGuide welcome your spine spider photos and observations. Your backyard sightings could help researchers better understand these beneficial arachnids and their changing habitats.

As development continues to reshape our landscapes, creating space for wildlife becomes increasingly important. By appreciating rather than fearing spine spiders, we take a small step toward living more harmoniously with nature. The next time you spot one of these spiny architects in your garden, give it a nod of appreciation for the free pest control services!

For those interested in our mortuary equipment solutions, we invite you to learn more about our custom-crafted products at American Mortuary Coolers. Like the spine spider with its perfectly engineered web, we take pride in creating equipment that performs its essential function with reliable precision.